Six Observations: COVID and America’s Laboratories of Democracy (Part One)

The virus reveals a striking pattern of variation, in part because of the way the disease has spread and in part because of the different responses of American governments at all levels. Consider how COVID, both in its outbreak and in vaccinations, reflects various approaches to governance in the U.S. (All of the data below are from late January 2021.)

Available data show that, so far, the country is lagging behind much of the rest of the world in battling the virus. Some states lag far behind others. And how best to achieve equity in delivering the vaccine to communities of color could impact the already difficult debates about race in the country.

The data reveal the impact of differences in governance across the United States, as well as the consequences of an initial strategy of the large-scale delegation of decisions from the federal government to the states combined with the lack of coordination among all levels of government—and between government and the private sector. It is an especially telling lesson that the first state to have vaccinated all of its nursing home residents, West Virginia, opted out of the federal program aimed at delivering the vaccine to nursing homes. One of the first vaccines to roll off production lines, Pfizer, was not part of the funding for Operation Warp Speed, the federal government’s effort to speed production of the shots (although the other early vaccine, Moderna, was.)

The data reveal, too, the stark differences that have emerged in the transition from the prior administration, which delegated virtually all important decisions to the states, and the current administration, which has begun by asserting a strong steering role for the federal government and a more active partnership with state and local governments. The charts in this blog—and in Part Two—provide a snapshot on the two strategies.

Going forward, leaders across the United States need to learn—quickly—how to tackle the enormous logistical challenges it faces. That’s going to take even stronger coordination between the federal government and the states, and it’s going to take a stronger governmental hand than perhaps some are prepared for. It will take a data system to allow people to sign up for the vaccine without camping out on their computer or wearing out their fingers with a telephone redial—and a system that will ensure that populations in need are not frozen out.

Acting soon is imperative. At the rate of vaccine roll-out in the first month, it will take a year to get at least one shot into the arm of every American and, with new variants of the virus quickly making the rounds, that job is more urgent than ever.

In this two-part blog, six observations will be made with accompanying lessons learned. Today let’s look at the data for the first three observations.

Observation 1: The disease has been especially deadly in the United States

For the death rate (after taking account of population differences), the virus has been more deadly in the U.S. than in almost any other country in the world: more so than in Peru and Spain, and more than twice as deadly as in Germany. The roots of the variations are hard to identify in broad terms. The United Kingdom found itself the center of a ferocious post-holidays outbreak; Italy was the center of a first major phase of the pandemic. But the inescapable conclusion is that the initial decentralized strategy of the United States produced markedly worse outcomes than in other countries, including other nations like Brazil and Germany with complex federal systems of government.

Source: Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Research Center, https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

Lessons:

- America’s initial struggles to develop a coherent national policy in dealing with the virus have put it among the nations most damaged by the outbreak.

- Other countries, including other countries with complex federal systems of intergovernmental relations, including Germany and Brazil, have done better.

Observation 2: Within the U.S., its impact has varied enormously

Within the United States, the death rate has diverged widely. In the early stages of the disease, it hit especially hard in New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts, before reaching the middle of the country in later stages.

Source: “Coronavirus in the U.S.,” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html

As of January 28, the total number of deaths in the U.S. was 429,312. If the country as a whole had followed the course of the 10 states with the highest death rate, the total would have been 663,000. Had we been able to follow the 10 states with the lowest death rate, the total would have been 160,000, or less than 40 percent of the actual rate.

The last Administration’s decentralized approach in the United States created enormous differences in the pandemic’s impact.

Lessons:

- Although comparing the outbreak across the states is a difficult enterprise because the virus spread so erratically, some states suffered far more than others, especially New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut, which saw the early outbreak.

- In time, however, the virus left no part of the country untouched, and some states that escaped the first stage of the outbreak (like the Dakotas) have suffered since.

- The virus affected some adjoining states, like the Carolinas, very differently.

- It will take some time to understand the lessons taught by states at the polar extremes of the outbreak, but some states clearly did a far better job than others in managing the virus.

- The fact that the states were, for the most part, left on their own meant that the opportunity to learn the best lessons—and learn them early— constrained the country’s capacity to slow the virus’s spread.

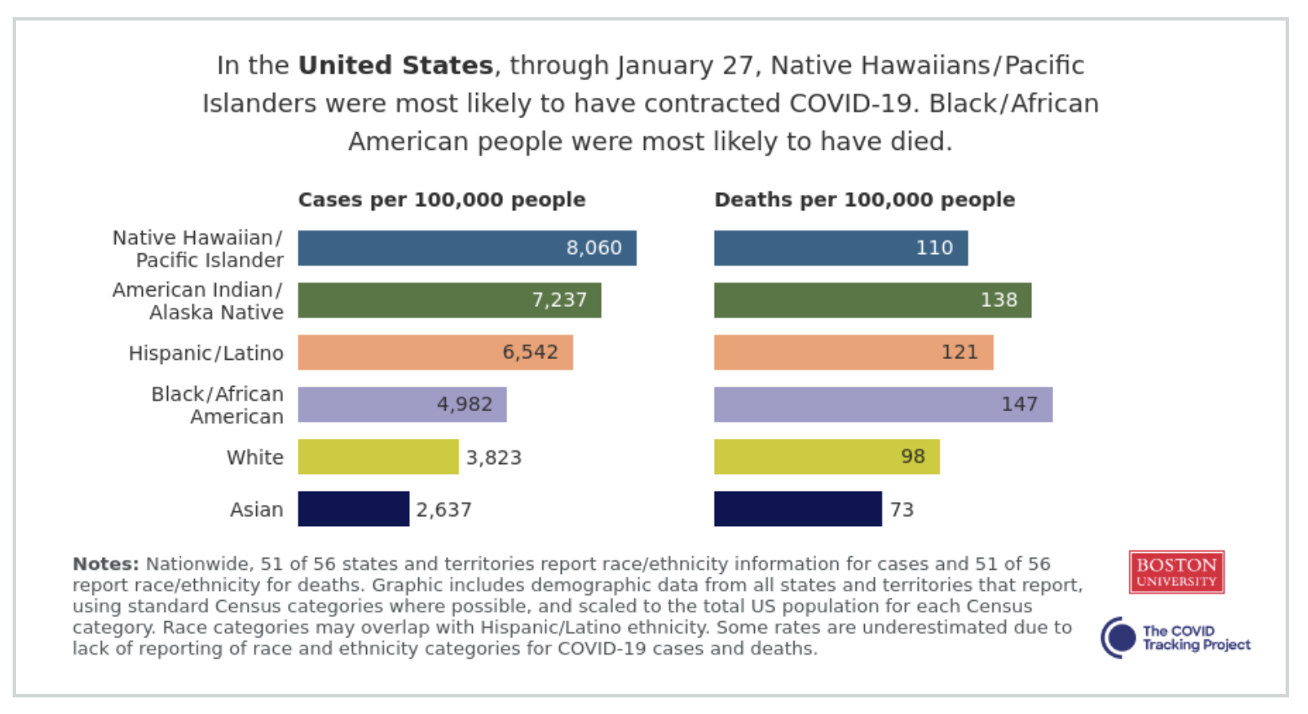

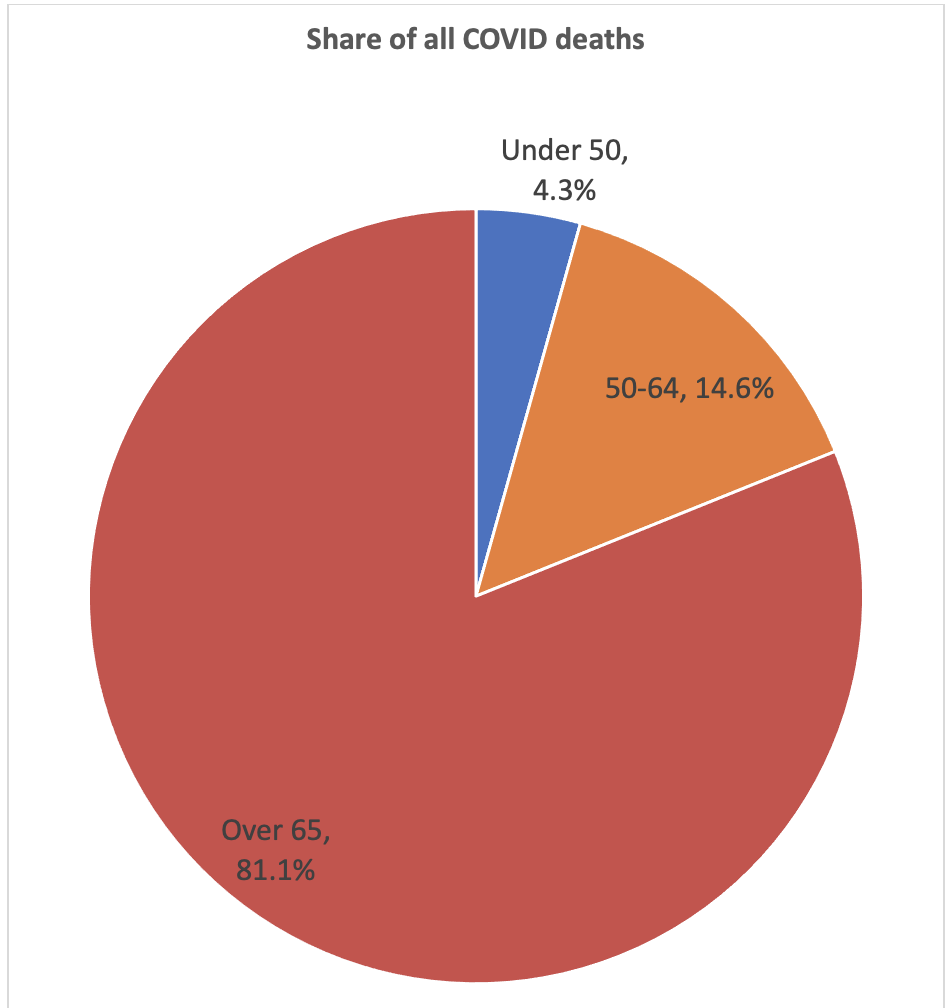

Observation 3: COVID has impacted some groups far more than others

The disease has especially vicious effects on older Americans. More than 80 percent of all deaths, in fact, have occurred in those over the age of 65.

Source: Centers for Disease Control, https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Provisional-COVID-19-Death-Counts-by-Sex-Age-and-S/9bhg-hcku

Men have accounted for 54 percent of all deaths, compared with 46 percent for women. And among some racial and ethnic groups, COVID has proven worse, especially for American Indians, Hispanics, and Blacks. These differences have compounded the geographic disparities in the pandemic’s outcomes and point to the implications of driving policy decisions from state and local governments.

Source: Johns Hopkins COVID Tracking Project, https://covidtracking.com/race/infection-and-mortality-data#AL

Lessons:

- The virus has certainly affected different parts of American society very differently. It has been especially deadly for older Americans and for people of color.

- It will be impossible to avoid perpetuating these problems if we do not take the lessons of the virus’s impact in framing the strategy for vaccinations. It will take a focused effort to inoculate older Americans and people of color to stop the virus—and to address the massive problems of inequity in the virus’ spread.

With these three observations, it is clear that the U.S. COVID death rates were higher than most other countries in the world as the nation at first lacked a coherent national policy. The states’ diverse experiences show how the virus left no part of the country untouched. And COVID has impacted older Americans, men, and people of color at a much higher rate than younger Americans, women, and Whites.

The next post will examine three additional observations, this time related to the COVID vaccinations.

Image courtesy of dream designs at FreeDigitalPhotos.net